I admit it. I’m a bit of a prepper. This is likely the case for anyone in the risk management profession, and even more so if you live on an island like I do (Maui). We can run out of food and supplies. Our critical infrastructure has little redundancy. If one power plant that is on the coast is taken out by a tsunami, cyber or any cause, most of the island is without power until it is fixed.

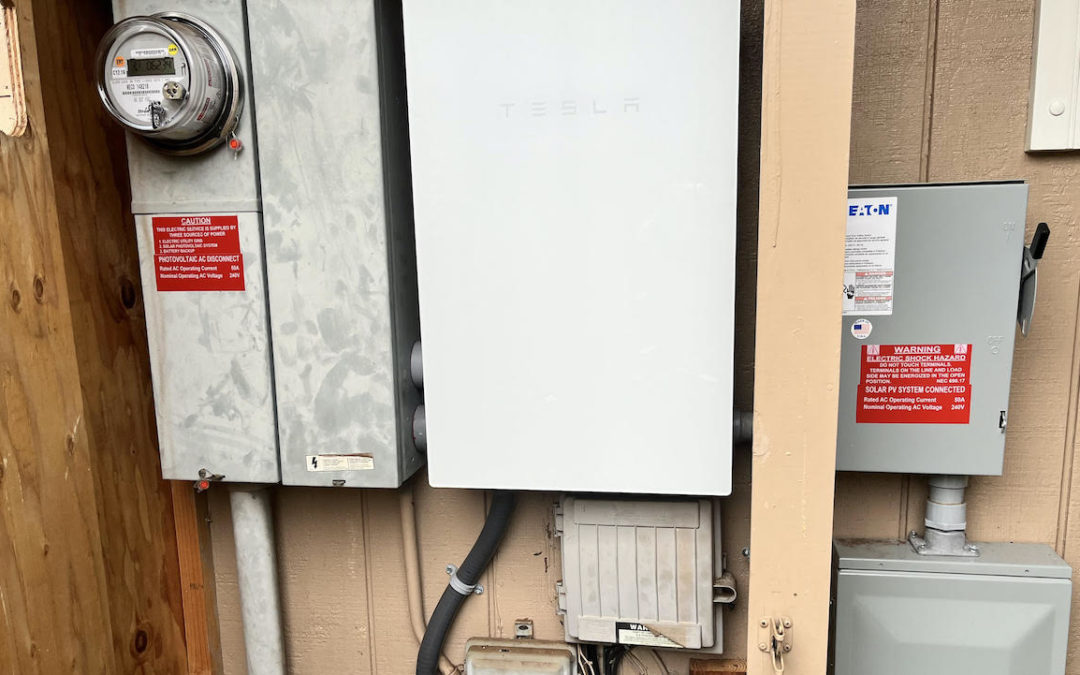

Hawaii has the highest cost for electricity in the US, and this drives the demand for solar. For the risk management minded, a solar system with battery storage is also a great way to address electric power availability risk. When the storm was coming in this weekend, I was feeling confident. We had food, water and other supplies. We had a water management system in place that would (should?) prevent flooding even in 20+ inches of rain. And we had our solar system with a Tesla Powerwall ready in case the power went out.

At 6:40 on Sunday the power went out. Not a surprise as it felt like a Category 1 hurricane, and we had 8′ high rivers running down the normally dry gorges, carrying trees and all sorts of debris. Our battery kicked in as it did during other power outages, so we still had the comfort of lights and other modern conveniences while it was howling outside.

This power outage lasted through the night and most of Monday. Longer than the previous outages, and Monday was also rain filled and cloudy limiting generation. In the late morning, the battery ran out. Not a problem. When the sun came out the solar would kick in and provide some power, or so I thought.

What happened was the solar and battery system was dead until the power came back on that evening. If this had been a multi-day or multi-week event, my system may have been useless because there is some setting or some misconfiguration that I was not aware of. It’s on my list for this week to figure out how to prevent this at the next outage, but it could have been a high consequence mistake for a long term outage.

This, like most times individuals or companies face a disaster, shows the importance of testing our resiliency and recovery plans. It also shows how carefully we need to try a variety of scenarios. My system was proven to work fine during an outage, but I never had an outage where I used all of the power in the battery. My assumption that it would just restart when the sun came out was wrong, at least as currently configured.

Back in the 90’s when I was involved in financial and other IT security in South Florida, many companies did extensive business continuity exercises for hurricanes. They would move the data center and operations out of Florida, and almost always found some things didn’t work as expected. I’m guessing the cloud makes this much easier today, but also likely introduces some other failures.

In the OT / ICS world I’ve seen business continuity tests focused on failing over to the backup site. This is a good test for most incidents, but not cyber incidents. The cyber incident business continuity exercise will sometimes include recovering a server and a controller or two. If this is you, you might want to rethink the rigor of this plan. What if you lost everything with an IP address? What if many of your Level 1 devices were bricked.

Even if you have a rigorous DR or business continuity test, you should look to vary the scenario every year and be creative. You may get lucky like I did and have your resilience failure be a minor inconvenience and lesson learned. Or you may pay a larger price.

“There are some things you learn best in calm, and some in storm.”

Willa Cather