How much do we really know about how to reduce outages due to a cyber attack?

We have over 1,000 of the worlds’ foremost experts on defining and implementing OT security good practice in this room. If we had 1000 of the foremost doctors from 300 years ago at this event, there would be numerous sessions on the best way to bleed a sick patient. Cuts or leeches? How much blood to take? How often to bleed?

Did you know that George Washington, the father and first president of the United States, was bled 4 times on the day of his death. They tried it once, he didn’t get better. Another doctor was called, and he was bled again. No improvement. Another doctor came, he was bled again. They took 80 ounces of his blood, 40% of his blood, and he died. The cause of death isn’t clear, but we know now that the bleeding didn’t help.

Are increasing calls for more information sharing, more detection, more enumeration, and more patching in OT … Is this our equivalent of more bleeding? I hope not and my analysis leads me to believe in some of these good practices, but we have about as much evidence, as much data, as those doctors did on the effectiveness of their good practice.

Now I know what you’re thinking. Silver bullet. Those doctors fell into the trap of thinking bleeding was a silver bullet. As we all know and have probably said, there is no silver bullet. Here’s the thing, almost no one really believes there’s a silver bullet. It’s a straw man that speakers, consultants and salespeople set up to knock down. Washington’s doctors weren’t foolish, they didn’t think bleeding was a silver bullet. They also followed the medical good practice of inducing blisters on Washington’s throat and legs.

How do we know when consensus good practice is correct?

One key step is to identify and admit what we don’t know. What is only informed conjecture or theory.

Consider cartography, map making. Prior to the 19th century, mapmakers had what historians refer to as horror vacui, a fear of leaving empty space on the map. You’ve probably seen maps with sea monsters on them to represent unknown geographic details.

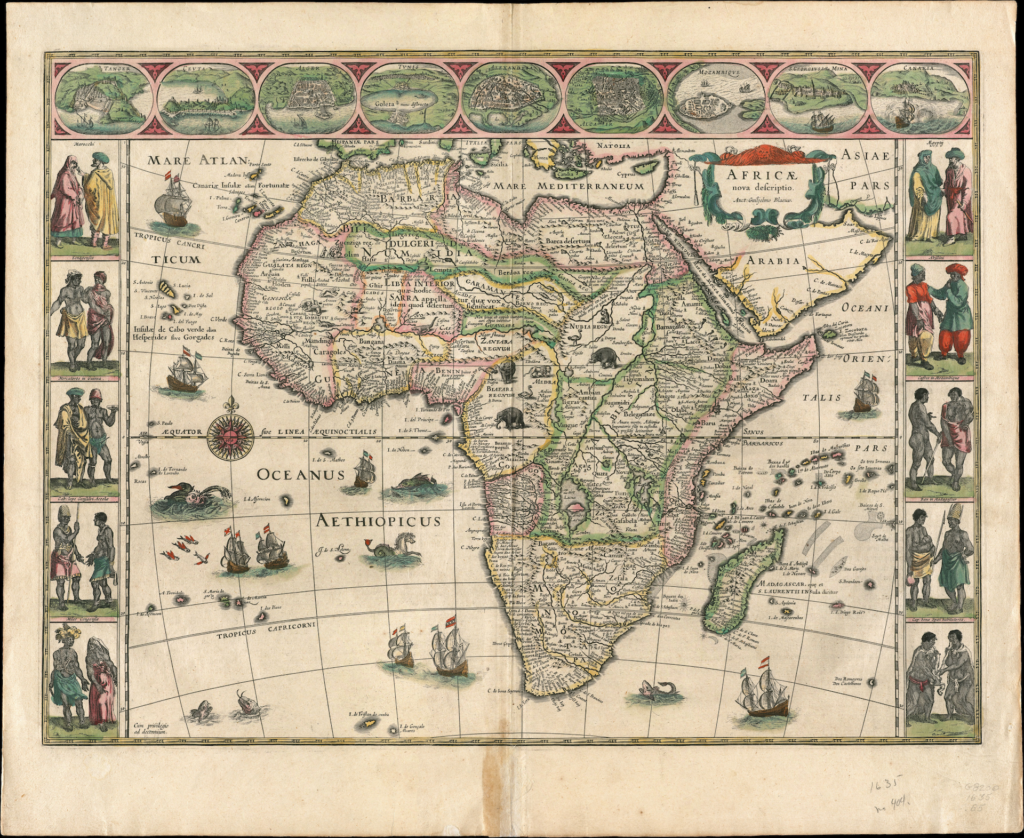

This is Dutch mapmaker William Blaeu’s map of Africa from 1635.

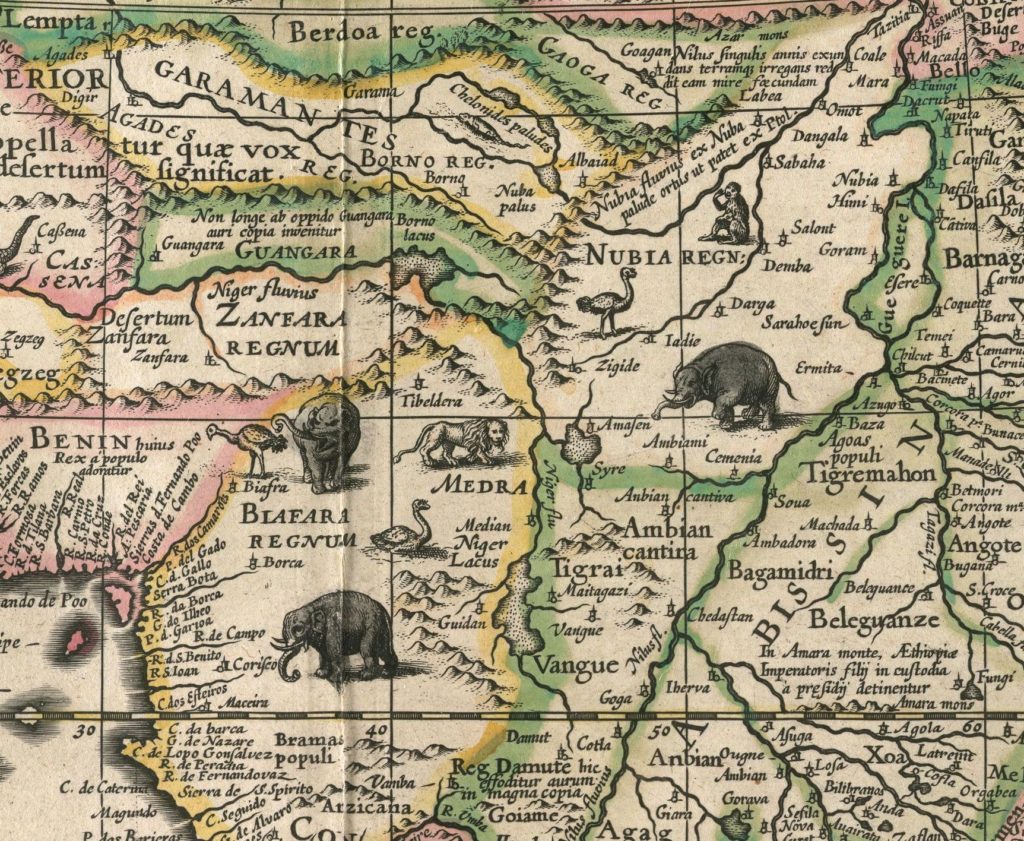

Let me zoom in on the center, you see elephants he put in the area that was unknown. This is misleading because you might think there is nothing there but animals. No rivers, lakes or mountains, but the mapmaker had no idea what was there. The addition of creatures to fill blank space wasn’t the worst problem. Mapmakers suffering from horror vacui also filled empty spaces with rumors, guesses or even their imagination.

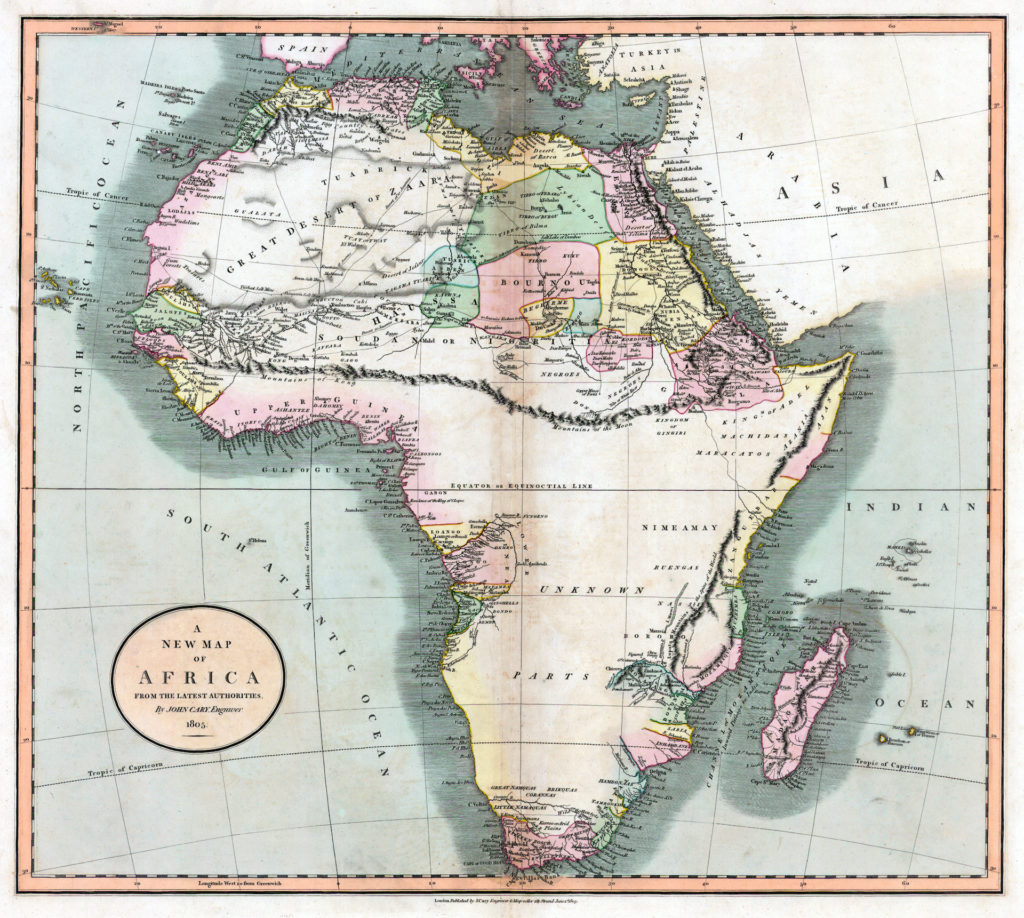

In 1805, 170 years of exploration since Blaeu’s map, the British mapmaker John Cary made an honest map of Africa with only information that was known. Look at all that empty space. 70% of Africa wasn’t known. Unexplored.

One of the most important advances in map making was admitting what wasn’t known. Getting past the horror vacui and instead embracing it. The acknowledgement of this blank space motivated explorers to go out and get the information to fill in those blank spaces.

We know very little about the actual effect on loss and mission related cyber risk that most of our current consensus OT security good practices achieve. We have our own version of horror vacui. We don’t want to admit that we really don’t know.

My estimate of our OT security map would be similar to John Cary’s map of Africa. We have some incident data, not a lot, but some on the effectiveness of an OT security perimeter, 2 factor authentication for remote access, removable media controls, and backup and recovery. Past this, the actual impact and risk reduction of most of our OT security good practices is theoretical and unproven.

This may sound depressing. I believe for this audience it’s an exciting opportunity. The tag line or mantra for S4 is Create The Future. It’s not learn good practices or attend what worked sessions. Most of you self selected to be here because you like to be on the leading edge. You’re an early adopter, an innovator or dare I say an explorer.

There is so much territory to explore. It’s like banking cybersecurity in the 80’s and 90’s, only with the added twist that we’re dealing with a wide range of industry sectors. More areas where you can explore and make your mark. The solutions, the right mix of risk reduction actions for hospitals are likely to be different than the mobile fleet in mining that are likely to be different than a refinery.

There are so many ideas and approaches to explore. Whether it’s trying to prove something is actually effective or bucking the conventional and unproven wisdom and trying something new.

Your preferred OT security control might in fact be highly effective. You analyzed it and believe in it. How can you prove it? How can you gain the knowledge and confidence to draw it on the map? What metric are you using to validate it?

OT security metrics are still rare. This is a problem. The OT security metrics I do see usually measure the effectiveness of implementing a specified security control, not the effectiveness of the control. The percentage of security patches applied, the number of utilities that are part of a detection effort, the number of ICS security advisories issued, the percentage of assets in the asset inventory. Let me be clear, these metrics are not wrong. We need to measure our implementation of a selected security control or task.

What we’re missing, and quite frankly what’s more important, are metrics that identify if a selected security control is worth it? Is it helping the company meet its mission. Its key performance indicators.

Gene Spafford and his co-authors of Cybersecurity Myths and Misconceptions share a study of over 3,000 hospitals that had a breach of patient information. A key metric for hospitals is the time it takes to get an electrocardiogram, an EKG, a test used to detect heart issues. The elapsed time from when a patient walks in with a potential heart issue to the time they get an EKG. Prior to the breaches, this elapsed time was the same for breached and non-breached hospitals. The breached hospitals added security controls to the process of accessing patient data. After this the time from the door to EKG at the breached hospitals increased by 2.7 minutes as compared to the non-breached hospitals and the death rate due to heart attacks in the breached hospitals with new security controls increased by .36%, 3 more people died per 1000 people that came into a hospital needing an EKG. This is an important metric, clearly related to the hospital’s mission.

This data doesn’t necessarily mean that the security controls implemented in the breached hospitals were wrong. To be right though, there would need to be metrics that clearly showed the security controls led to improvements in achieving the hospital’s mission. For example, if annual loss of hospital service operation time due to a cyber attack was much lower, let’s say decreasing from 36 hours to 2 hours, in hospitals with the security controls, then the security controls might be warranted. On the flip side, even if the controls reduced cyber incidents by 90%, the controls could be a mistake if those incidents had a negligible impact on the hospital as compared to 3 more people per 1000 dying. We need to measure the impact of the OT security good practice on the organization’s key mission metrics.

I understand there are good theories and reasonable analysis behind our good OT security practices, and the recommendations we make. As many of you know, I’m not shy about providing my analysis with clients and in articles and podcasts.

For example, I have long pushed back on the value of patching about 90% of OT cyber assets due to the insecure by design issue. This is unproven theory on my part just as is the much more common guidance that everything in OT should be patched at a frequent interval.

We find our own unproven analysis compelling. Even more so when most voices are singing together in a harmonic chorus. So did the doctors who bled patients for years. They had a consensus scientific model of the human body structured around four humors, the most important being blood.

Many organizations already have key performance indicators, the number of deaths and safety incidents, outages with customer impact, financial loss. We need to be tracking cyber incidents that have affected the company’s key performance indicators before and after new security controls are in place. Even better, is when a sector can agree on these metrics and share them like the hospital EKG example. This is the best and most needed information sharing.

Honestly identifying and acknowledging what we don’t know is the first step in going from where we are to today to creating a secure and reliable OT world in the future.

The second step is to go exploring in the blank space. Into the unknown.

One of my favorite stories of exploration is Richard Burton and John Speke’s search for the source of the white Nile. It’s fortunate that ICS security explorers don’t need to undergo the illness and physical hardship that Burton & Speke did. Although sometimes I think our community has as much interpersonal drama as those two had.

Eventually after years filled with horrific illness, battles, near starvation, politicking and personal strife, Speke discovered that Lake Victoria is the source of the white Nile.

The funny thing about this discovery is it already had been discovered. Indigenous people had known about and lived near this lake for centuries, they called it Nyanza. Arab traders had been traveling to and from the lake for many decades. The called it Ukerewe and knew of a large, deep and broad river that ran out of it. The European countries and their explorers didn’t know about it, but it had already been discovered.

What discoveries have already been made in areas of study outside of OT and ICS security that we’re going through unnecessary great hardship to re-discover?

There is a tendency to treat ICS security as if it is a special flower. Different than everything else. We can’t do what IT, or any T, is doing in cybersecurity because OT is different!

Those closest to engineering and operations look favorably at gaining knowledge from the field of safety. Safety is different than OT security, but we’re not afraid to look there and use what works. We should be looking at economics, human behavior fields such as psychology, actuarial and insurance, risk management, political science, statistics and IT and anywhere else that might hold answers.

When you explore you don’t always succeed. Sometimes you get stopped well before your goal. Sometimes you get where you wanted and find nothing, or what you find disproves the reason you went exploring. While many would call these failures, they’re not. The explorer either learns something to alter their approach and try again, still believing they’re right, or they prove a hypothesis, a theory, was wrong. This has huge value.

Where are the glorious and celebrated failures in OT cyber security and risk? Where have we said we thought this would work, and it didn’t? What have we rejected based on the data?

This is so rare in cybersecurity in general and OT in particular. An idea can’t fail if there is no criteria or measurement for success except for the activity taking place. I always chuckle when I see Cyberstorm or other information sharing exercises take place. You can write the press release on how it succeeded before it started, because success was viewed as the exercise happening.

We tend to accumulate good security practices and are now putting them into a bucket called cyber hygiene. If there is a view that cyber risk is not adequately addressed, we need more security controls. Rarely do we take a security control out. We only add.

A great counter example is the longstanding requirement to change passwords. I am shocked and impressed that they actually had the courage to say changing passwords frequently isn’t reducing risk. Get rid of this requirement. Can we be this open and brave? Brave to identify and track metrics that might show what we’ve been recommending isn’t working, or worth the resources? Brave enough to look outside our field of expertise and re-discover and use what is known there?

If you’re finding your work boring or repetitive, exploration is a way to get past that. Exploration is where the pioneers and influencers live. It will be exciting and new, whether it succeeds or fails. You can rekindle your passion for your job, your field of study, and maybe discovering something amazing.

My hope is that you will take the opportunity this week amongst all this talent, all these experiences, the ideas in the sessions, and the conversations under the palm trees, take the opportunity to move well beyond conventional OT security good practice. Go exploring. Explore the idea that these good practices may not be achieving what you hope. Explore how you will measure them. And most importantly explore the giant, wide, unknown blank space in OT security and risk management.

This event, S4, is designed to help attendees know what’s coming in the next 1 – 3 years. To get ahead and be able to predict the future for yourselves, your career and your company. The best way to predict the future is to create the future. This is what I’m counting on the 1000 of you here at S4 23 to do. Thank you.d